By Matthew Sabatino, Prachi Vinata Murarka, Prema Shakti

The Sárñgadhara Samhitā is a text containing classical Āyurvedic formulations. Specifically, the second division of the text laid out classical formulations.

Madhyama Khaṇḍa is the 2nd division of the Samhitā and is comprised of 12 chapters. It deals with Pañca vidha Kaṣāya Kalpanā (5 types of Kaṣāyas), Svarasa (fresh juices of herbs), Kalka (paste of medicinal herbs), Kvathana (hot decoctions of medicinal herbs), Śīta (cold infusions) and Phāṇṭa (hot infusions). Preparations of various types of medicinal formulations like Cūrṇa (herbal powders), Vāṭī (tablets), Lehyas (confections), Tailas (oils), Āsava and Ariṣṭa (fermented herbal preparations), Rasa Auṣadhas (minerals and metallic preparations) etc are described in this section.

Opium and cannabis were used in classically formulated medicines, as mentioned in the Sárñgadhara Samhitā.

Opium and Cannabis

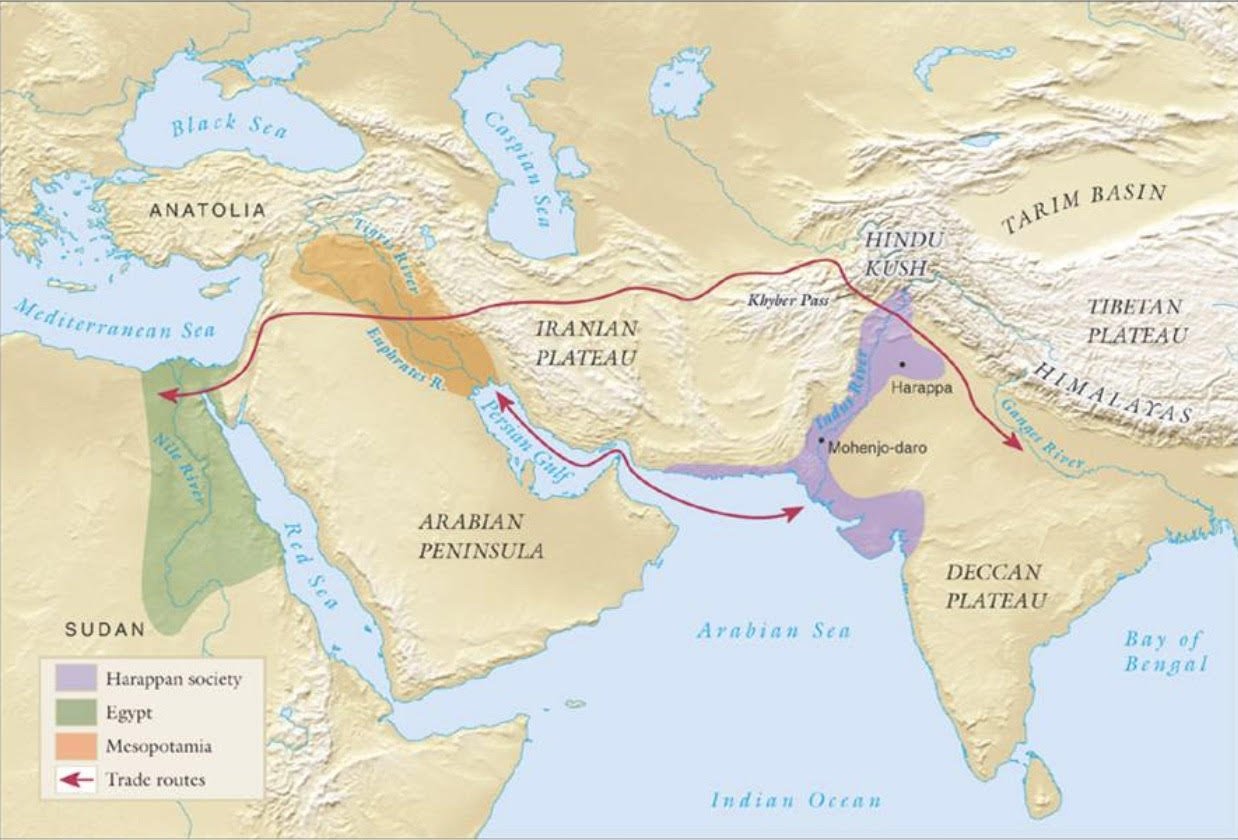

Purified opium is used in eight Āyurvedic preparations and is said to balance the Vāta and Kapha doshas and increase the Pitta dosha. It is prescribed for diarrhea and dysentery, for increasing the sexual and muscular ability, and for affecting the brain. The sedative and pain-relieving properties of opium are considered in Āyurveda. The use of opium is found in the ancient Āyurvedic texts, and is first mentioned in the Sárñgadhara Samhitā (1300-1400 CE), a book on pharmacy used in Rājasthān in Western India, as an ingredient of an aphrodisiac to delay male ejaculation. It is possible that opium was brought to India along with or before Muslim conquests. The book Yoga Ratnākara (1700-1800 CE, unknown author), which is popular in Mahārāṣṭra, uses opium in a herbal-mineral composition prescribed for diarrhea. In the Bhaiṣajya Ratnāvalī, opium and camphor are used for acute gastroenteritis. In this drug, the respiratory depressant action of opium is counteracted by the respiratory stimulant property of Camphor. Later books have included the narcotic property for use as analgesic pain reliever.

The latex of poppy seeds can be used as a natural cleanser to treat gut disorders such as IBS, diarrhea and chronic fever.

Morphine obtained from poppy seeds is used in treating severely painful states like in deep trauma wounds, cancer patients etc.

Codeine alkaloid obtained from opium seeds was once used in most cough syrups but was later replaced by better chemical compositions merely because of its addictive nature and sleep inducing properties.

Kāminī Vidrāvaṇa Ras is an ayurvedic medicine used for treating men’s health problems. It is useful in erectile dysfunction, impotence, and premature ejaculation. The main effects are observable in cases of premature ejaculation. It delays ejaculation and improves men’s stamina.

INGREDIENTS (COMPOSITION)

Kāminī Vidrāvaṇa Ras contains following ingredients:

Ingredient Quantity & Ratio

Śuddha hiṅgu 1 Part

Śuddha gandhaka 1 Part

Anacyclus Pyrethrum – Akārakarabha 3 Parts

Zingiber Officinale –Śuṇṭhī (ginger) 3 Parts

Syzygium Aromaticum – Lavaṅga (Clove) 3 Parts

Crocus Sativus – Kesara (Saffron) 3 Parts

Piper Longum – Pippalī (Long Pepper) 3 Parts

Myristica Fragrans – Jātīphaḷa (Nutmeg) 3 Parts

Myristica Fragrans – Jāti patrī (Mace) 3 Parts

Santalum Album – Śveta Candana (White Sandalwood) 3 Parts

Papaver Somniferum – Śuddha Ahiphena 12 Parts

Piper betle – Tāmbūlapatra svarasa (betel leaves juice) Q.S.

Cannabis

Cannabis indica/sativa is also mentioned in the ancient Āyurveda books, and is first mentioned in the Sárñgadhara Samhitā as a treatment for diarrhea. In the Bhaiṣajya Ratnāvalī it is named as an ingredient in an aphrodisiac.

Āyurveda prescribes the use of cannabis for the healthy and patients in six forms viz: powder (Cūrṇa), round Pills (Modaka), tablets (Vāṭī), linctus (Leha), boiled with milk (Dugdhapaka) and decoctions (Kada). In addition, it is prescribed and traditionally used in various food forms viz, sweet drink (Śarabata), burfee, and laddoo. Cannabis is also used for chewing and it is added to the betel leaves (Pāṇ). Some people used it as smoke (Dhūmrapāna).

Currently, Cannabis is most commonly taken in 3 different forms in India. As the attitude towards cannabis has fluctuated greatly over time in India (largely due to Muslim and British colonizers) these definitions have morphed over the years depending on what is ‘legal’ and what is available.

Bhaṅgā is generally leaves cured in a specific way and typically boiled with milk and spices.

Chāra is resin, akin to kif or hash.

Gaṅjā is flowers, usually taken for pleasure but also made into many different medicines. Seeds and roots are used in some formulations as well.

Āyurveda recommends the use of Cannabis after processing (boiling with milk etc.). In Āyurvedic works, over 50 important formulations containing Cannabis have been described:

In some of these formulations, the part of the Cannabis plant to be used is clearly specified. In some of them the seeds of the plant are used. In some formulations, Āyurvedic herbs, metallic and mineral ingredients (Bhasma) are added for synergistic effect. Cannabis is indicated both for healthy individuals and patients. But the former is used as an aphrodisiac and also as a rejuvenating agent.

In the Sárñgadhara Samhitā, fresh extracts of bhaṅgā were employed medicinally, and it was linked to opium: “Drugs which act very quickly in the body first by spreading all over and undergoing change later are vyavāyī; for example, bhaṅgā, ahiphena”. Additionally, cannabis was cited as an intoxicant and employed as the primary ingredient in a therapeutic mixture of herbs: “This recipe known as jātīphalādi cūrṇa if taken in doses of one karpa, with honey, relieves quickly grahaṇī (sprue [chronic diarrhea]), kāsa (cough), śvāsa (dyspnoea), aruchi (anorexia), kṣaya (consumption) and pratiśyāya [nasal congestion] due to vāta kapha (rhinitis).”

The 15th-century Rājavallabha, written by Sūtradhāra Maṇḍana for Raṇa Kumhha of Mewar, attributed several additional qualities to cannabis: “Indra’s food (i.e., ganja) is acid, produces infatuation, and destroys leprosy. It creates vital energy, the mental powers and internal heat, corrects irregularities of the phlegmatic humour, and is an elixir vitae. It was originally produced, like nectar from the ocean by the churning with Mount Mandara, and in as much as it gives victory in the three worlds, it, the delight of the king of the gods, is called vijaya, the victorious. This desire-fulfilling drug was obtained by men on the earth, through desire for the welfare of all people. To those who regularly use it begets joy and destroys every anxiety.” It is added, “The Rahbulubha alludes to the use of hemp in gonorrhoea.”

“In Bhāvaprakāśa (A.D. 1600), cannabis is mentioned as ‘anti-phlegmatic, pungent, astringent and digestive’. On account of these marked narcotic properties it was probably also used as an anesthetic, sometimes combined with alcohol.

Cannabis is indicated in Āyurveda for following conditions:-

(1) Sprue syndrome (Grahaṇī)

(2) Male and female sterility (Bandhyatva)

(3) Impotency (Napunisakatva)

(4) Diarrhoea (Atisāra)

(5) Indigestion (Ajīrṇa)

(6) Epilepsy (Apasmāra)

(7) Insanity (Unmāda)

(8) Colic pain (Śūla)

Āyurvedic formulations like Jātīphalādi Cūrṇa, Madananada Maḍaka etc. with cannabis as an ingredient.

Jātīphalādi Cūrṇa Formulation composition:

Jatiphala Myristica fragrans Sd. 1 part

Lavaṅga Syzygium aromaticum Fl.Bd. 1 part

Elā (Sukshmaila) Elettaria cardamomum Sd. 1 part

Patra (TejaPatra) Cinnamomum tamala Lf. 1 part

Tvak Cinnamomum zeylanicum St.Bk. 1 part

Nāgakeśara Mesua ferrea Stmn. 1 part

Karpūra Cinnamomum camphora Sub.Ext 1 part

Śvetā Candana Santalum album Ht.Wd. 1 part

Tila Sesamum indicum Sd. 1 part

Tvakkṣīrī (Vamisha) Bambusa bambos S.C 1 part

Tagara Valeriana wallichii Rt. 1 part

Amlā (Āmalakī) Emblica officinalis P. 1 part

Talisam Abies webbiana Lf. 1 part

Pippalī Piper longum Fr. 1 part

Pathyā (Harītakī) Terminalia chebula P. 1 part

Sthūlajīraka (Upakuñcikā) Nigella sativa Sd. 1 part

Citraka Plumbago zeylanica Rt. 1 part

Śuṇṭhī Zingiber officinale Rz. 1 part

Viḍaṅga Embelia ribes Fr. 1 part

Marica Piper nigrum Fr. 1 part

Bhaṅgā (Vijayā) Śuddha Cannabis sativa Lf. 20 parts

Śarkarā Cane Sugar 40 parts

Lf.=Leaf;P.=Pericarp;Rt.=Root;Fr.=Fruit;Rz.=Rhizome;Sd.= Seeds;St.=Stem;St. Bk.= Stem Bark;Fl. Bd.=Flower Bud.

Resources:

https://www.easyayurveda.com/2016/11/02/sharangdhara-samhita/

https://www.theayurveda.org/ayurveda/benefits-afeem-papavar-somniferum

https://www.ayurtimes.com/kamini-vidrawan-ras/

https://everydayayurveda.org/ayurvedic-cannabis/

https://www.sanjivaniwellness.org/perspective-of-medical-cannabis-in-ayurveda/

https://www.ayurmedinfo.com/2012/07/19/guduchyadi-kashayam-benefits-dosage-ingredients-side-effects/

https://www.bimbima.com/ayurveda/jatiphaladi-churna-health-benefits/1373/